On Dec. 6, 1273, 750 years ago, St. Thomas Aquinas did the unthinkable: He permanently abandoned work on his magnum opus, the Summa Theologiae, after many years of intensive labor and just months shy of its completion.

Thomas was at the height of his fame, a counselor to popes and kings. In just two decades of prodigious writing, he had produced a torrent of eight million words, gathered into three monumental theological syntheses, countless commentaries, magisterial disputed questions, unforgettable hymns and more.

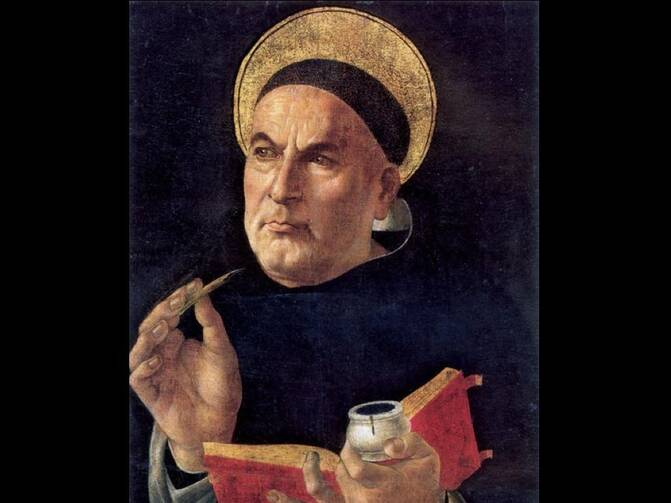

When he was a student of St. Albert the Great 25 years earlier, he earned the nickname “the Dumb Ox,” both for his large stature and for his inveterately quiet disposition. St. Albert, for his part, prophesied that the Ox’s bellow would one day sound through all the world. A quarter of a century later, it did.

Why, then, did he go silent again? What reduced his flow of texts to naught?

St. Albert prophesied that the Ox’s bellow would one day sound through all the world. A quarter of a century later, it did. Why, then, did he go silent again?

The physical explanation

Thomas’s workload had been crushing. He was no slouch to begin with, and the previous several years saw him churning out his sprawling Summa with the help of a team of secretaries, while writing no fewer than a dozen commentaries on Aristotle; this was in addition to his regular teaching duties. Did he have a stroke from the strain of so much writing?

Whatever happened, it did indeed sap his strength. He used the remainder of December 1273 to recover at his sister Theodora’s house.

Nonetheless, Thomas still had his wits about him, for not only was he able to carry on a conversation until the end of his life, but two months later he composed one precious last piece of theological writing in a brief exposition on the relation of human freedom and divine foreknowledge for the monks at Monte Cassino. (His biographer Jean-Pierre Torrell, with some exaggeration, says it is “perhaps the clearest” exposition of the subject; we could say, more justly, that it is a perfectly lucid if not altogether complete account, which is understandable given the fact that it was written while traveling.)

The letter to the abbot, which Thomas wrote to accompany the exposition, is a piece of high rhetorical art, revealing that Thomas was very much in command of the gift of speech and remained suffused with human feeling.

Aquinas's secretary received a most unsettling and unexpected reply: “Everything I have written,” Thomas told him, “is straw.”

The spiritual explanation

For his part, Thomas’s explanation of the silence was not physiological but spiritual. As often happened, he entered an ecstasy during Mass. Earlier in the year, on Passion Sunday, while he was celebrating Mass before many witnesses, the experience lasted so long that brothers had to intervene so that Mass could be finished. On this day, the feast of St. Nicholas, Thomas celebrated Mass as usual in the chapel of St. Nicholas in San Domenico Church in Naples. When Thomas’s friend and secretary Reginald brought him back to his senses, he was transformed.

“Come, and let us get to work,” said Reginald. “I cannot do any more,” replied Thomas. “But, Master, you are close to finishing the Summa.” Then he received a most unsettling and unexpected reply: “Everything I have written,” Thomas told him, “is straw.”

It is tempting to think that with this dismissal, Thomas rejected his theological work. Yet, though straw is worthless to us, in the Middle Ages it was the stuff of hats and roofs and beds, not to mention the food of livestock. So Thomas was not saying his writings are worthless. Their utility is not questioned. Prodded further by Reginald, Thomas offered this clarification. “Everything I have written seems to me as straw in comparison with what I have seen.”

The ox, like the cow, chews its cud, and such rumination is a privileged metaphor for human contemplation, for the act of carefully savoring and appropriating truth. Perhaps, without being too clever, we might even risk the observation that while one is ruminating and has one’s mouth full, speaking is out of the question.

Hence the Dumb Ox offers no repudiation of his straw, useful as it is to others, but he has moved on to higher things, which require one’s whole mind and strength for meditation.

In leaving the Summa incomplete, the illusion of a self-contained and ultimate system, an illusion in every way antithetical to Thomas’s own intentions, is decisively undermined.

A telegraphed end

In fact, Thomas wrote the supersession of the work of theology into the very ground plan of the Summa. In the first question of the Summa, he says that still higher than theological wisdom and philosophical wisdom is the wisdom that comes from above as a gift of the Holy Spirit. With the author Dionysius the Areopagite, he describes this as suffering or undergoing the things of God.

Theology is the application of human reason to the principles of the faith. But the participatory experience of faith, available even in this life thanks to God’s free initiative, carries us further than our human reasoning alone can go.

For just as science, the rational investigation of the various parts of reality, is completed in philosophy’s rational investigation of the whole and its ultimate cause, and philosophy, in turn, finds completion in theology’s application of philosophical principles to the divinely revealed truths of the faith, so theology, finally, achieves completion here below when its human mode of thinking yields to experiential contact with God’s illuminating presence.

Thomas at one point likens the use of philosophy in theology to the transformation of water into wine. To complete his analogy, we could say that at this moment of his life there occurred the further transformation of theological wine into the Eucharist itself.

Thomas freely chose to leave the Summa unfinished. In leaving it incomplete, the illusion of a self-contained and ultimate system, an illusion in every way antithetical to Thomas’s own intentions, is decisively undermined.

“For then only do we know God truly,” Thomas wrote before even starting on the Summa, “when we believe Him to be above everything that it is possible for man to think about Him.”

Thomistic mysticism

Today we might call the Dec. 6 encounter “mystical,” but only if we divest it of the accretions of subjectivity that infect our modern consciousness. For what is decisive is precisely the de-centering of self before the divine Other rather than some exalted feelings or experiences of oneself.

Here one need only recall the profound meditation on friendship with the Holy Spirit that Thomas offers in his most personal work, the Summa Contra Gentiles. Beyond the Aristotelian analysis of friendship, Thomas invites us to consider the importance of conversation and intimacy with one’s friends, conversation and intimacy that takes on its most pregnant significance in friendship with the Holy Spirit:

Of course, this is the proper mark of friendship; that one reveal his secrets to his friend…. Therefore, since by the Holy Spirit we are established as friends of God, fittingly enough it is by the Holy Spirit that men are said to receive the revelation of the divine mysteries.

Three-quarters of a millennium after Thomas Aquinas went mute, we do well to recall that the bellow of the Dumb Ox is loudest in its silence.

A silent witness

The final silence, rather than an awkward end, is the fitting fulfillment of his whole mission.

From start to finish, Thomas offers us a way of thinking and seeking geared toward the primacy of experiencing the mysterious God, a way opened by faith, nourished by reasoning, fed by encounter and leading toward the full knowledge afforded the saints in heaven.

In the Commentary on Boethius’s De Trinitate, written soon after becoming a master of theology, Thomas says that the theological master cannot and must not openly speak about all that he knows lest others fall into error or fail to seek the truth for themselves. He quotes an anonymous source as an authority: “Hidden things are sought more avidly, and the concealed seems more venerable, and things long sought are cherished the more.”

As we approach another feast of St. Nicholas, three-quarters of a millennium after Thomas Aquinas went mute, we do well to recall that the bellow of the Dumb Ox is loudest in its silence.

*Chad Engelland is a professor of philosophy at the University of Dallas and the author of several books, including The Way of Philosophy and Phenomenology.

https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2023/11/16/aquinwas-summa-theologiae-unfinished-246490?utm_source=piano&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=35191&pnespid=sLhrUztJL6AW3_DAr22.DcudvB2uCcpvNfC1wOh3qRhmzn9Sr2B0R6D5kdG9ZvxpxOEaxGop

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário